Sea-Level Rise

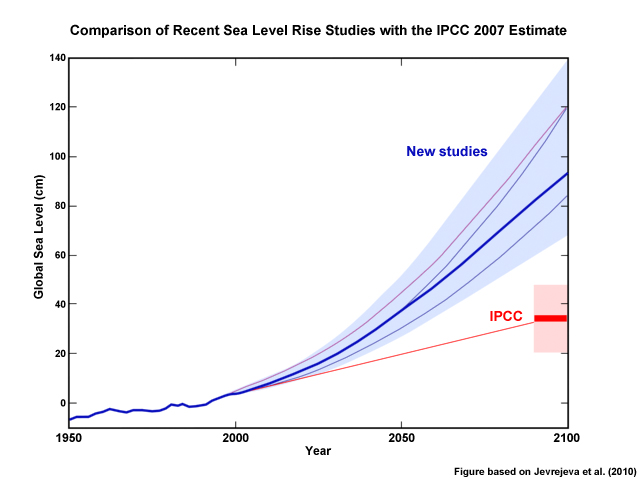

The oceans will continue their rise in the coming century. In their 2007 report, the IPCC estimated that the global average sea level will rise by about 9 to 20 in. (22-50 cm) by 2100 (relative to 1980-1999) under a range of greenhouse gas emissions scenarios. It is important to note that these estimates assumed that melting from Greenland and Antarctica would continue at the same rates as observed from 1993-2003. However, new research suggests that the IPCC predictions may be too low, and that sea level rise could be closer to 3 ft (1 m).

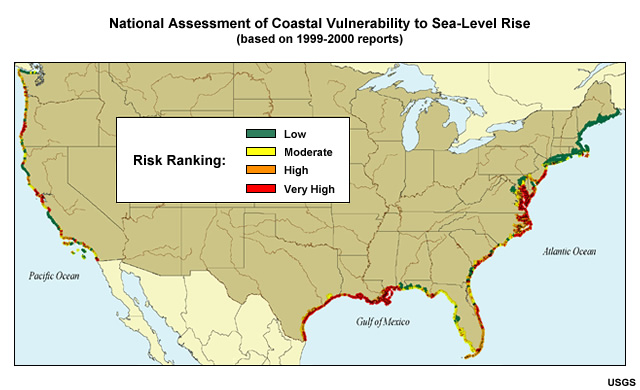

If seas rise two feet (0.6 meters), the United States could lose 10,000 square miles (26,000 square kilometers) of land surface, mostly on the Gulf and Atlantic coasts. If they rise three, they will inundate Miami and most of coastal Florida.

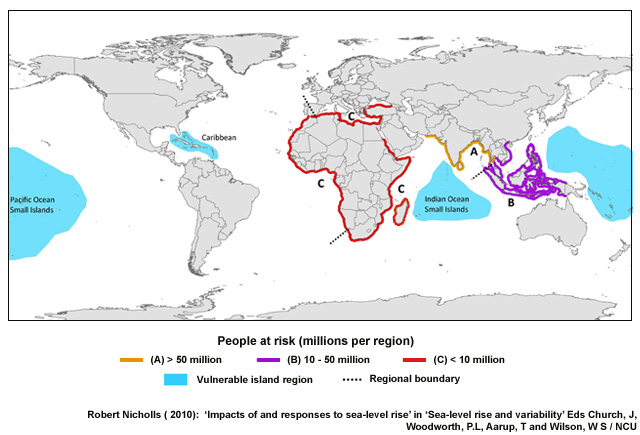

This map highlights regions that are most vulnerable to coastal flooding based on a scenario for the 2080s that assumes a global sea level rise estimate of 18 in. (45 cm). Nearly half of the world's population lives in low-lying coastal areas, and continued population growth along coasts increases vulnerability from sea-level rise, storm surge, and flooding.

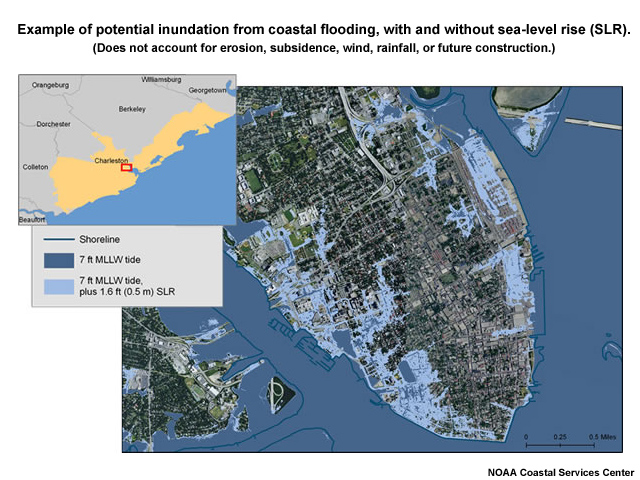

Even a small amount of sea level rise can produce major changes for coasts. In low-lying areas, a foot and a half of vertical rise (0.5 m) can cause inundation far inland, as illustrated in this image, which shows how Charleston, South Carolina would be impacted by that magnitude of sea level rise.

Other effects of sea level rise can include saltwater intrusion into freshwater aquifers that provide drinking water and loss of coastal wetlands and their ecosystems. One estimate projects 17-43% of U.S. wetlands could be submerged, of which more than half would be in Louisiana. Though new wetlands will form farther inland, their total area will probably be reduced, which would put New Orleans and other coastal cities at even greater risk from hurricane storm surge.