Snow and Ice

Snow and ice reflect the sun's energy back to space. Without this white cover, more water can evaporate into the atmosphere where it acts as a greenhouse gas, and the ground absorbs more heat. Snow and ice are melting at rates unseen for thousands of years, and this has profound climate consequences. As with air temperature, most of the melting in our 100 years or so of official record keeping has occurred after 1980.

Spring snow cover has decreased since 1922 at an average rate of about 2% per decade in the Northern Hemisphere, including a steep 5% drop during the 1980s. River and lake ice don't last as long as they used to either. As permafrost melts in the vast northern tundra, trees locals colorfully call "drunken trees" are falling over and buildings are crumbling as the ground disintegrates beneath them.

With a few exceptions, glaciers have been shrinking across the globe. In Glacier National Park, for example, there were 150 glaciers in 1850. Today, there are 26. In Switzerland, the Tortin Glacier, which supported a local ski area, shrank so much that the Swiss put a city-block sized insulating sheet over the glacier's edge to slow its retreat.

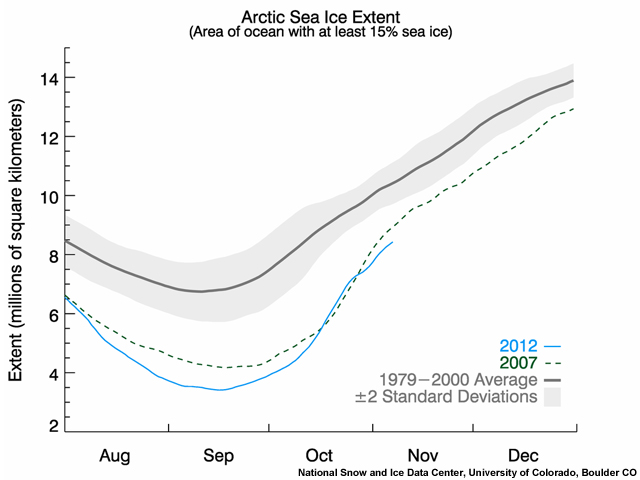

Sea ice is dwindling too, especially in the Arctic. Satellites have observed winter Arctic sea ice shrink by about 3-4% per decade from 1979, and an even higher rate in summer.

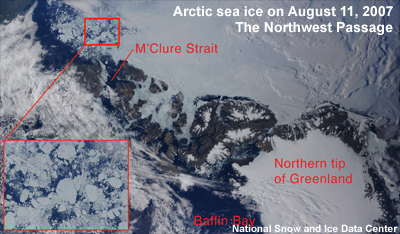

In summer 2007, the Northwest Passage north of Canada became navigable for the first time as the polar cap melted to its lowest level to that date—30 years faster than IPCC scientists had predicted.