How Sure Are Scientists?

IPCC Confidence/Probabilities

Signs, Effects, Causes

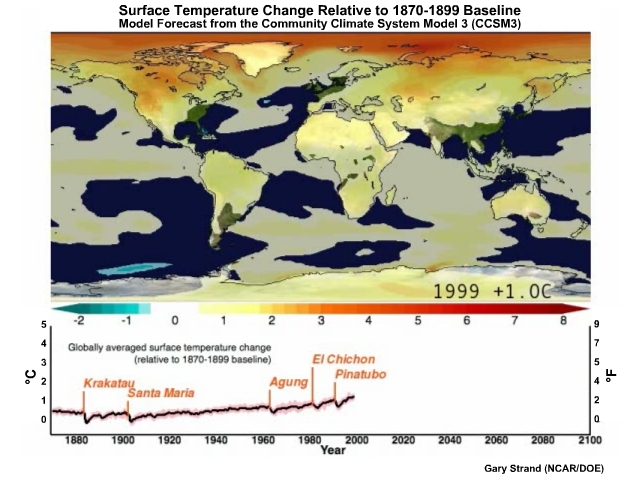

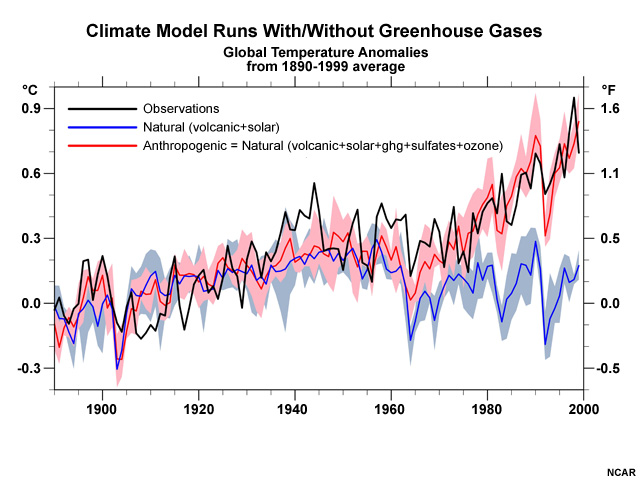

Though the greenhouse gas hypothesis has been thoroughly poked and prodded, no credible competing explanation has emerged that fits the bulk of the evidence. If greenhouse gases had remained unchanged, scientists found that solar and volcanic activity during the last half century should have produced cooling, not warming. Thus, the IPCC concluded it is "very likely", or greater than a 90% chance, that something other than natural causes is at work.

Here are the IPCC's confidence levels in other signs and effects of climate change, as well as for the evidence that humans are responsible.

Signs Content

IPCC Confidence in Signs of Climate Change | ||

| Signs | Certainty | % Probability |

| Warming of the climate system | Unequivocal | 100% |

| Less frequent cold days, cold nights, and frosts, more frequent hot days and hot nights over most land areas | Very likely | >90% |

| During the second half of the 20th century, highest average Northern Hemisphere temperatures in at least the past 1,300 years | Likely | >66% |

| Global area affected by drought has increased since the 1970s | Likely | >66% |

Observed Effects Content

IPCC Confidence in Observed Effects of Climate Change | ||

| Effects | Confidence Level | Quantitative Confidence |

| Recent warming strongly affects terrestrial biological systems, including earlier spring events and poleward and upward shifts in plant and animal ranges | Very high | At least 9 out of 10 chance of being correct |

| Increases in number and sizes of glacial lakes | High | About 8 out of 10 chance of being correct |

| Increasing ground instability in mountain and other permafrost regions | High | About 8 out of 10 chance of being correct |

| Increased runoff and earlier spring peak discharge in many glacier and snow-fed rivers | High | About 8 out of 10 chance of being correct |

| Warming of lakes and rivers in many regions, with effects on thermal structure and water quality | High | About 8 out of 10 chance of being correct |

Human Attribution Content

IPCC Confidence in Human Attribution | ||

| Evidence humans are responsible | Certainty | % Probability or Quantitative Confidence |

| Global average net effect of human activities since 1750 is warming | Very high confidence | At least 9 out of 10 chance of being correct |

| Solar + volcanic forcings have produced cooling in last 50 years | Likely | >66% |

| Most of observed increase in global average temperatures since mid-20th century due to increases in greenhouse gases from human activities | Very likely | >90% |

| Human-caused warming over last 30 years has a had a visible influence on many physical and biological systems | Likely | >66% |

Confidence in Future Projections

The IPCC found there is "high agreement" and "much evidence" that with current policies and practices, global greenhouse gas emissions will continue to grow over the next few decades. They also agreed that if we stopped burning fossil fuels today, the Earth would continue to warm due to long-lived gases and oceanic heat that are already in the system. So some amount of climate change and its impacts is inevitable.

| Scenario | Best Estimate | Likely range |

| Low emissions | 3.2°F (1.8°C) | 2.0-5.2°F (1.1-2.9°C) |

| Medium emission | 5.0°F (2.8°C) | 3.1-7.9°F (1.7-4.4°C) |

| High emissions | 7.2°F (4.0°C) | 4.3-11.5°F (2.4-6.4°C) |

The big unknown is how much and how soon we will reduce greenhouse emissions in the future. For the 2007 IPCC report, modelers looked at a number of scenarios that made various assumptions about fossil fuel use, economic growth, population, and technologies. Their estimates for temperature change by the end of the century are shown in the table and the previous animation.

Confidence in Future Impacts

| Effect | IPCC Likelihood | % Probability, Confidence |

| 20-30% of plant and animal species become extinct if global average temperatures exceed 2.7-4.5°F (1.5-2.5°C) | Likely (extinction rate) Medium confidence temperatures will exceed 2.7-4.5°F (1.5-2.5°C) | >66% 5 out of 10 chance |

| By 2080, millions experience floods due to sea-level rise | Very high confidence | At least 9 out of 10 chance |

| Frequency of warm spells and heat waves increases | Very Likely | >90% |

| Frequency of heavy precipitation increases | Very likely | >90% |

| Areas affected by drought increase | Likely | >66% |

| Intense tropical cyclone activity increases | Likely | >66% |

| Millions experience adverse health effects, especially in undeveloped countries | Likely | >66% |

Impacts from higher temperatures are difficult to evaluate, since they depend not only on how warm things get, but also on how fast humans adapt. This, in turn, depends on such things as national wealth and access to education and health care. This table describes impacts that the experts are reasonably confident about.

Two Positions

It's Not Happening

Although many statements that climate change is bogus are based on false or incomplete information, there have also been some legitimate scientific criticisms of climate change science. It's important to separate one from the other, particularly since misinformation can be stubbornly persistent, especially on the Internet. For example, you can find several websites and blogs where someone states that global warming is due to increased energy from the sun. However, observations of the sun for the past 30 years show no increase in its energy production.

The important questions posed by reputable climate scientists who disagree with most of their peers are these:

- Do we really know enough about the drivers of climate to be really sure that we know what causes change?

- Are scientists grossly underestimating the complexity of the Earth system?

- Are climate models good enough to accurately simulate the complex climate system?

- Are there processes that will limit warming naturally by producing a negative feedback?

These questions are important, and science thrives on debate that fuels further investigations. It is always possible that questions raised will lead to new information that will change our perspective. However, to date the majority of climate scientists are convinced that enough of the puzzle is visible to conclude that the world is warming and human activities are largely responsible.

It's Worse Than We Think

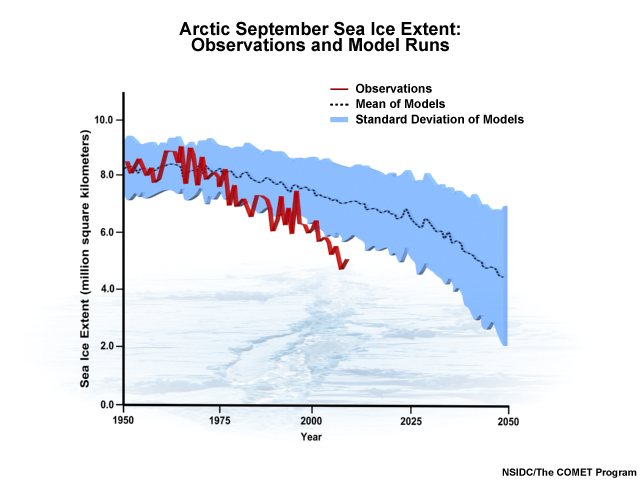

On the other hand, some climate scientists think IPCC has been far too conservative. They believe warming in the next century will be much greater than the IPCC assessments indicate, and there is some evidence to support this. For example, Arctic sea ice is melting much faster than scientists predicted. Also, actual fossil fuel emissions in recent years have exceeded all but the highest IPCC projections.

Since 2000, they have grown four times faster than in the 1990s. Some argue that the IPCC near-future assumptions about global energy use are too optimistic. A recent study also concludes that the IPCC estimates were too rosy with regard to how quickly developing countries will be able to afford technologies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Scientists in this camp also say sea levels may rise far more than we anticipate because our calculations aren't taking into account the unexpectedly large melting and disintegration of the Greenland and Antarctic Ice Sheets. They also point out the last IPCC report was limited to already-published and peer-reviewed research, and the conclusions had to be reached by consensus. This is bound to produce a cautious, conservative estimate for the future, they say.

Consensus?

The IPCC is a very important process for determining consensus on climate change, but there are other ways to find out what scientists who know the most about climate really think. In 2007, the Statistical Assessment Service at George Mason University conducted a random survey of U.S. scientists who:

- Are members of either the American Meteorological Society (AMS) or the American Geophysical Union (AGU)

- Are listed in American Men and Women of Science, 23rd Ed.

- Live in the U.S.

- Have expertise and/or professional experience in the area of climate science

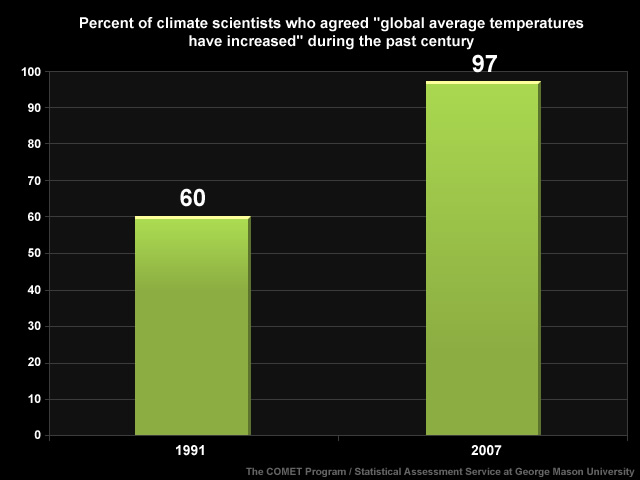

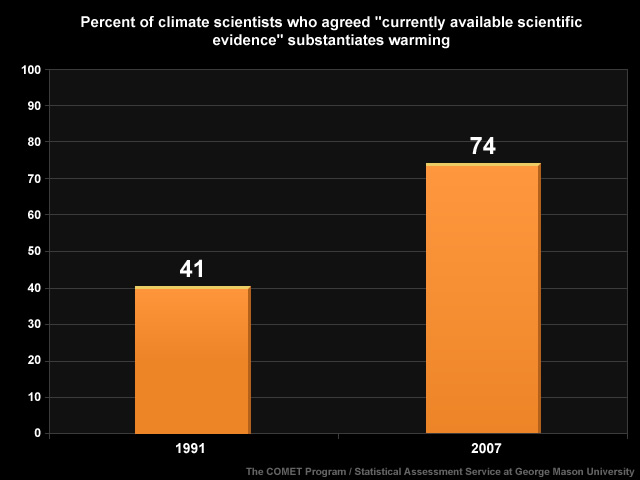

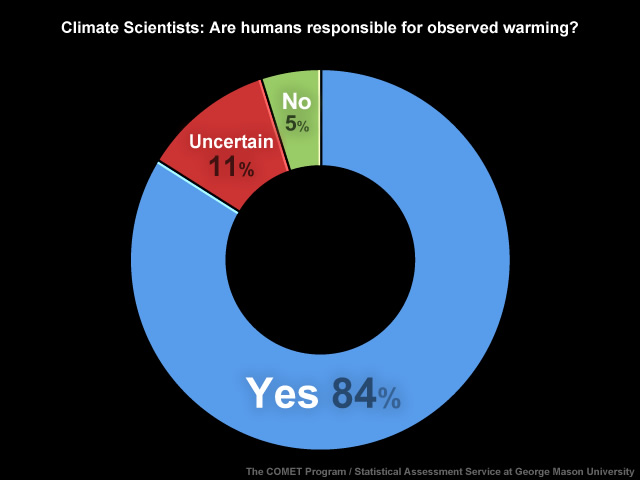

Ninety-seven percent of the 489 respondents agreed that "global average temperatures have increased" during the past century. That's up from 60% in 1991. Eighty-four percent said they personally believed human-induced warming is occurring, and 74% said "currently available scientific evidence" substantiates this, up from 41% in 1991. Only 5% said that human activity doesn't contribute to greenhouse warming, and 11% were uncertain. So the survey does indicate the bulk of climate scientists—those most knowledgeable about the field—now agree that human activity contributes to global warming.

As with all science that affects our lives, we need to be educated consumers. Do your homework, starting with the IPCC reports. All of the reports provide interesting information, although they are lengthy and quite technical. The AR4 Synthesis Report (www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/syr/ar4_syr.pdf) is easy to read and provides a good summary of the other reports. Also look at the work from other authoritative sources such as the National Academy of Science (NAS), the American Meteorological Society (AMS), the American Geophysical Union (AGU), the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), etc..

When looking at information (particularly on the Internet) look at the source of the information—is it likely to be biased one way or the other? If so, look for alternative views from other sources and see what they say. Ask questions—if you read something that seems to contradict something else, then dig deeper. Trace the origins of the statement to the original source. Is it a peer-reviewed journal or something less exacting? What are the credentials of the author—is it a scientist with climate expertise?